By Peter, Master Electrician | PRO Electric plus HVAC

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT (BLUF)

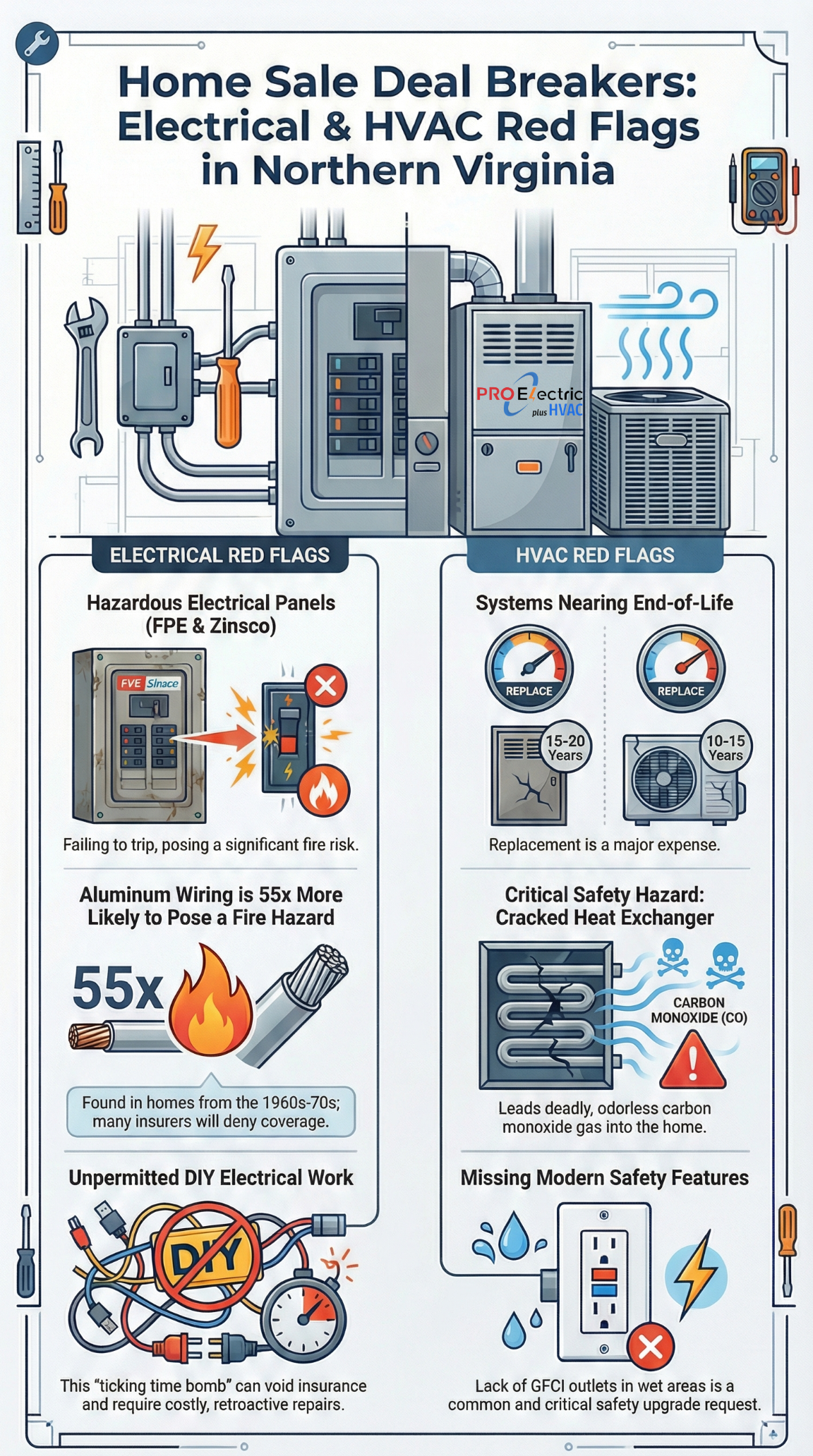

Homebuyers and sellers in Northern Virginia often face critical electrical and HVAC issues that can make or break a real estate deal. As a Master Electrician serving Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, and Arlington Counties, I’ve seen firsthand how outdated wiring, aging HVAC systems, code violations, and unpermitted work can derail a home sale if not properly inspected and addressed. In this guide, I’ll walk you through eight common reasons why an electrical or HVAC inspection may be necessary as a contingency in a home purchase or sale. Each chapter draws on real-world cases, local county nuances, and authoritative sources from Realtor® associations to legal cases to explain how these issues cause contract failures and what steps you can take to prevent them. Whether you’re dealing with an old fuse box in Arlington, a failing AC in Fairfax, DIY wiring in Loudoun, or a code violation in Prince William, this guide will help you navigate the due diligence needed to keep your transaction on track.

If you are considering buying or selling a home, this article is written for you.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Outdated Electrical Systems in Older Homes – Why old wiring (knob-and-tube, aluminum) and antiquated breaker panels (like FPE or Zinsco) in Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, and Arlington homes often trigger inspections and sale contingencies.

- Chapter 2: Unpermitted and DIY Electrical Work – How illegal or uninspected electrical renovations can cause contract delays or failures, with examples of Northern Virginia sellers forced to fix code violations or lose the sale.

- Chapter 3: Aging HVAC Systems Near End-of-Life – Common HVAC lifespan issues in local homes (from Arlington bungalows to Ashburn colonials), and why buyers insist on inspections or replacements for old furnaces and AC units.

- Chapter 4: HVAC Functional Problems and Safety Concerns – Specific heating and cooling problems (inefficiency, carbon monoxide risks, inadequate cooling) that surface during inspections in Virginia homes, often leading to repair negotiations or terminated contracts.

- Chapter 5: Code Compliance and Safety Upgrades – The impact of building codes (GFCI/AFCI requirements, smoke detectors, minimum service amperage) in Northern Virginia, and why bringing a home up to code becomes a contingency issue in many sales.

- Chapter 6: Home Inspection Contingencies and Deal Breakers – How electrical/HVAC issues are the #1 cause of home sale contract failures, including real cases of buyers walking away due to costly defects, and the role of contingencies in protecting both parties.

- Chapter 7: Local County Perspectives – A closer look at Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, and Arlington County-specific factors: housing stock, climate, and regulations that influence the need for specialized inspections (with neighborhood examples from Reston to Leesburg).

- Chapter 8: Case Studies and Best Practices – True stories of contract pitfalls (like a required panel replacement in Portsmouth, VA) and expert tips – from pre-listing inspections to negotiating repairs – to ensure a smooth closing in Northern Virginia real estate transactions.

- FAQs

- References

Chapter 1: Outdated Electrical Systems in Older Homes

Why It’s a Problem: Northern Virginia has a mix of historic homes in areas like Old Town Alexandria, Leesburg, and Arlington that still feature outdated and unsafe electrical systems, such as knob-and-tube wiring, aluminum circuits, and ungrounded outlets. These aging systems pose serious fire and shock hazards, especially when overloaded by today’s modern appliances and electronics. Buyers (and their lenders and insurers) are rightly concerned about old electrical infrastructure – it can be a deal-breaker if not properly inspected and remedied. I’ve lost count of how many times a home sale in Fairfax City or Falls Church hit a snag because the electrical panel was from the 1950s, or the wiring couldn’t pass a safety inspection.

Common Outdated Wiring Issues: In homes built before 1970 (plentiful in Arlington’s older neighborhoods like Clarendon or in Fairfax County’s Annandale and Springfield areas), you often find knob-and-tube (K&T) wiring and early-generation circuit panels. K&T wiring, used in the early 20th century, lacks a ground wire and has insulation that degrades over time – it’s a clear fire hazard once it becomes brittle or overloaded by modern use. Likewise, many Northern Virginia houses from the 1960s have single-strand aluminum branch wiring, which was a mid-century substitute for copper. Aluminum wiring connections tend to oxidize and loosen, leading to overheating or arcing that can ignite fires. In fact, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission found that homes with pre-1972 aluminum wiring are 55 times more likely to have fire-hazard conditions at connections than homes with copper wiring. That statistic is alarming – and I’ve had buyers in Vienna and McLean immediately demand an electrician’s inspection or a full rewire upon learning a home has aluminum circuits. Insurers also consider aluminum wiring a defect; some insurance companies will deny or void coverage until it’s properly remedied. This essentially forces the issue to be addressed as a contingency, because a buyer can’t close (or get a mortgage) on a house they can’t insure.

Another red flag is old service panels. Many mid-century homes in Fairfax and Prince William County (e.g., in older parts of Manassas or Woodbridge) were built with 60-amp fuse panels, which are grossly undersized for modern needs. Today, the electrical code requires at least a 100-amp main service in new homes, and 200-amp is common for safe capacity. If a home still has only 60-amp service or an antiquated fuse box, it will not only struggle to power central HVAC, kitchen appliances, and home offices – many insurers will flat-out refuse to insure a house with less than 100-amp service due to the fire risk. I’ve seen home sales fall apart in Herndon and Centreville when an astute home inspector opens the panel and finds an old 60A fuse box; no buyer’s insurer will sign off without an upgrade, so the seller either has to negotiate a heavy credit for a new service or risk the buyer walking.

Hazardous Panels (FPE and Zinsco): Even if the service amperage is sufficient, the brand and age of the breaker panel matter. Homes built in the 1970s and early 1980s in areas like Burke Centre (Fairfax) or Sugarland Run (Sterling, Loudoun) sometimes have Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) “Stab-Lok” panels or Zinsco panels. These panels are notorious in the industry – they frequently fail to trip during overloads, posing a significant fire hazard, and they’re no longer UL-listed or manufactured. There are plenty of them still in Northern Virginia homes, and it’s important to get them replaced as soon as possible. In my experience, any home inspector who sees an FPE or Zinsco panel will flag it in the report, often with language like “have panel evaluated by licensed electrician,” which is code for “this panel is unsafe and should be replaced”. In one Fairfax sale I handled, the discovery of an FPE panel prompted the buyer to demand a $2,500 seller credit for a new panel (in line with typical replacement costs). If the seller had refused, that outdated electrical panel could cause financially stretched buyers to bolt – especially in today’s high-priced, high-interest-rate market. The National Association of Realtors even warns that an “outdated electrical panel” is the kind of costly surprise that can make buyers walk away at the last minute. Thus, the presence of these old panels often triggers a contingency: the sale might be contingent on replacing or upgrading the panel, or the buyers may reserve the right to terminate if the seller won’t address it.

Local Examples: Throughout Northern Virginia, you’ll find pockets of older homes and corresponding electrical issues. For instance, Arlington County neighborhoods like Lyon Park and Del Ray (adjacent to Alexandria) have 1920s-1950s bungalows – many have been renovated, but those that haven’t often hide K&T wiring in the walls. Similarly, Fairfax County has communities such as Annandale, Fairfax City, and Falls Church with 1950s-60s houses where original wiring or panels are still in place. Over in Loudoun County, historic towns like Leesburg, Middleburg, and Waterford feature 19th-century and early-20th-century homes – these may have seen partial electrical updates, but it’s not uncommon for an inspection to reveal a subpanel wired with old cloth-insulated conductors or an attic with post-and-tube remnants. Even Prince William County has the “old town” sections of Manassas and Dumfries with aging infrastructure. In all these cases, prudent buyers will make the contract contingent on a thorough electrical inspection and often on the seller either repairing hazards or offering a credit. As a Master Electrician, when I inspect such a home, I provide a detailed report of deficiencies – e.g., bare or brittle wires, lack of GFCI protection, over-fusing, and so on – which count as “material deficiencies” since they could affect a reasonable person’s decision to buy. This report often becomes part of the negotiation under the home inspection contingency.

Bottom line: If you’re buying or selling an older home in Northern Virginia, expect outdated electrical components to be a major contingency issue. From a 1940s Arlington Colonial with knob-and-tube, to a 1970s Fairfax split-level with an FPE panel, these are exactly the kind of problems a home inspection is meant to uncover. They must be addressed for the deal to proceed – either through repairs, upgrades, or contract concessions – because no buyer wants to move into a fire hazard, and no lender or insurer wants to underwrite one either.

Chapter 2: Unpermitted and DIY Electrical Work

Why It’s a Problem: In Northern Virginia’s hot real estate market, many homeowners have attempted DIY electrical projects or hired cheap, unlicensed handymen to save money. Areas with lots of homeowner renovations – say, the basements finished by owners in Burke, the additions in older Vienna homes, or the garage workshops in Leesburg – often have electrical work done without proper permits or by unlicensed electricians. While these fixes might “work” on the surface (the lights turn on, the outlets have power), they frequently violate code and pose hidden dangers. During a home sale, unpermitted or substandard electrical work is a ticking time bomb: it can fail the home inspection outright, and moreover, any significant unpermitted electrical modification will likely need to be corrected (with permits) before closing, or else the buyer’s lender and insurer may balk. I’ve seen buyers walk away from contracts in Chantilly and Arlington upon discovering that the home’s previous owner had rewired the kitchen or added a new circuit illegally – they simply didn’t want to inherit the liability and hassle.

Code and Legal Implications: All Northern Virginia jurisdictions (Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, Arlington, and the cities within them) follow the Virginia Uniform Statewide Building Code, which incorporates the NEC (National Electrical Code) standards. This means any new wiring, circuit additions, service panel changes, or even adding outlets requires a permit and inspection by the local county’s building authority. For example, if a homeowner in McLean (Fairfax County) or Ashburn (Loudoun County) finished their basement and added electrical circuits without permits, they have technically performed illegal work. Skipping permits might save time or fees initially, but it “can lead to big problems: unpermitted work not only poses safety risks if done incorrectly, but can also void insurance claims or delay the sale of the house”. Indeed, unpermitted electrical work often must be brought up to code retroactively when it’s found – meaning the seller might be forced to open up walls and have the work re-done (with proper permits) as a condition of sale. I always advise sellers: if you did electrical work yourself or hired someone under the table, disclose it and be prepared for an inspection. If you’re a buyer, your home inspector or electrician should look for telltale signs: wires spliced outside of junction boxes, non-GFCI outlets near sinks, overloaded breaker panels, missing permits on recent renovations, etc. These are red flags that work was done without oversight – and you absolutely want a licensed electrician (like me) to inspect further.

Impact on Transactions: Unpermitted electrical work can cause contract contingencies or even outright failures. Here’s a scenario I encountered in Fairfax County: A homeowner in Springfield had installed outdoor lighting and a hot tub circuit on their own. When selling, the buyer’s inspector noted the subpanel was not up to code and there were no county inspection stickers. The buyer’s offer became contingent on the seller either obtaining a permit and passing inspection for that work or removing it entirely. Fairfax County, for example, explicitly states that installing or upgrading any electrical equipment without a permit is illegal and can incur fines. Ultimately, that seller had to hire us to rip out the DIY wiring and redo it with a permit, costing time and money to satisfy the contingency and close the sale. Had they not, the deal would have fallen through, as the buyers were unwilling to take on unpermitted (and potentially unsafe) electrical systems. This isn’t an isolated case: non-compliant electrical work can fail inspections or delay your home from being listed or sold to a potential buyer. I’ve had Realtor partners in Herndon and Woodbridge call me in a panic when a pre-listing home inspection finds double-tapped breakers, improper wiring in an addition, or missing GFI outlets – all signs that someone cut corners. In many of those cases, we’ve had to rush in to correct these issues so the sale could proceed.

Buyers, for their part, are often advised by their agents to be cautious of homes sold “as-is” because it could hide unpermitted work. They may include a specific contingency for a licensed electrician’s inspection in the contract if the home’s MLS listing hints at “recent owner improvements” but no permit history. If that inspection finds violations, the contingency allows them to demand the seller fix it or they walk. From a legal standpoint, Virginia’s disclosure laws require sellers to inform buyers of known material defects – and unpermitted, dangerous wiring certainly qualifies as material in most cases. Even if the seller tries to dodge disclosure by saying “I’m not aware” or selling as-is, a savvy buyer will conduct due diligence. And if something disastrous happens later (say a fire due to that unpermitted wiring), the seller could face a lawsuit for failure to disclose or for negligence, especially if they clearly did the work themselves.

Real Case in Virginia: A noteworthy example of how serious this can get is a case from Portsmouth, VA (not in NoVA, but illustrative). In that situation, the buyers purchased a home only to discover it had a Federal Pacific panel (known to be unsafe) that would not pass current code. The city of Portsmouth essentially did “not permit” a sale to close with that panel active. The buyers consulted a lawyer because the inspector had missed it. The guidance was that the panel needed immediate replacement (at ~$1,200–$2,500) and that multiple parties – the inspector, the title company, potentially the seller – might bear responsibility for the oversight. This case underscores a key point: if unpermitted or shoddy electrical work is discovered after closing, it can lead to legal battles over who pays for remediation. It’s far better for all involved to catch and address these issues before closing, which is exactly why inspection contingencies exist.

Preventive Measures: If you’re a seller, the best practice is to proactively address this issue. Have a licensed electrician do a pre-listing electrical inspection. In Northern Virginia, we at PRO Electric offer a “Real Estate Partner Program” in which we inspect a home’s electrical system for sellers and provide a report on any code or safety issues. This way, you can fix them proactively or disclose them upfront. It’s much cheaper than a deal falling apart. If you’re a buyer under contract, definitely use your home inspection window to investigate electrical quality. You can even ask the seller about permit history: in Fairfax and other counties, permits are public record – I often pull records to see if that recently remodeled kitchen in a Fair Lakes townhouse had an electrical permit; if not, I know to look closely at the wiring quality.

In summary, unpermitted electrical work is a common cause of additional inspections and contract contingencies in our region. Buyers want assurance that all work is safe and legal; sellers who ignore this risk delays, price reductions, or lost sales. As I always tell clients: the few hundred dollars for a proper permit and inspection is “cheap insurance” – it ensures the work is done right and keeps your home sale on track. Cutting corners on electrical work isn’t worth the potential cost of a failed real estate deal (not to mention the safety risk to your family).

Chapter 3: Aging HVAC Systems Near End-of-Life

Why It’s a Problem: Heating and cooling systems have finite lifespans, and in many Northern Virginia homes on the market, the HVAC equipment is at or near the end of its useful life. As a result, HVAC inspections become crucial contingencies – no buyer wants to be surprised by a failing furnace in the first winter or a dead A/C in the first heat wave after closing. I’ve observed that in places like Loudoun County’s booming subdivisions (Ashburn, Sterling, South Riding) and Fairfax County’s established neighborhoods (Vienna, Springfield, Reston), houses built in the early 2000s or late 1990s are now coming on 20–25 years old – meaning their original HVAC systems are often past their prime. In fact, industry data shows that a typical central air conditioner or heat pump lasts about 10 to 15 years, and a furnace lasts about 15 to 20 years, depending on maintenance. So, a home for sale in 2026 that was built in 2005 likely has HVAC equipment at that 20-year mark. Buyers see it as a major expense looming on the horizon, which is why they frequently include a contingency for an HVAC inspection or service. In Northern Virginia’s climate – hot, humid summers and chilly winters – a reliable HVAC isn’t optional; it’s essential for comfort and health.

Identifying an Old System: Real estate agents and home inspectors in our area are very attuned to HVAC age. A good listing agent in, say, Fairfax, will often list the age of the HVAC in the marketing remarks if it’s new (“New HVAC in 2023!”). If that line is missing and the unit looks dated, buyers get suspicious. During a home inspection, the inspector will read the serial numbers to determine the manufacturing years of the furnace and condenser. I’ve seen inspectors in Arlington immediately point out in their report, “The AC is 22 years old, past its typical lifespan.” According to one home-buying guide, the average lifespan of an HVAC system is 15 to 25 years, so it’s quite common for houses on the market to have older HVAC systems in place. In other words, a large percentage of home sales in Northern Virginia involve HVAC units that are due for replacement soon. That’s why many buyers make their offers contingent on a professional HVAC evaluation – or they plan to negotiate a credit for replacement. For example, I recall a sale in Herndon where the buyers noticed the home’s original 1998 furnace. They used the home inspection contingency to bring in an HVAC technician (from our team) to fully assess it. We found the heat exchanger was rusted and the efficiency was poor. The buyers then requested a $5,000 credit to go towards a new furnace and AC. The sellers, recognizing the system was 25 years old, agreed rather than lose the deal.

Efficiency and Modern Standards: Another reason an aging HVAC triggers inspections is energy efficiency and refrigerant concerns. Many older A/C units (pre-2010) use R-22 Freon refrigerant, which has been phased out (manufacture banned as of 2020) due to environmental regulations. Servicing those units is increasingly expensive because R-22 is scarce. A buyer of a home in Centreville or Gainesville might specifically ask, “Does the AC use R-22?” If yes, they know that if it ever needs a recharge, it’ll cost a fortune – thus, they may push for replacement as part of the sale. In Arlington and Alexandria rowhouses I’ve worked on, we often encounter 15+ year-old heat pumps that still cool, but not efficiently. Home inspectors will note “HVAC is functional but near end of life; budget for replacement.” While Virginia’s home inspection contingency does not count mere age as a “deficiency” (if it’s working, it’s technically not a defect), a savvy buyer can still use the information as leverage. They might not be able to demand that the seller replace a working 20-year-old system (since it’s “grandfathered” as functioning, even if not up to modern standards), but they can ask for a home warranty or a price reduction to account for the likely replacement cost. It’s common in our region for buyers to request a one-year HVAC home warranty paid by the seller if the system is old – effectively as insurance in case it breaks after closing.

Signs and Inspection Findings: During an HVAC inspection (whether as part of a general home inspection or a specialized check), technicians look for functional issues that often plague older systems. Some things we frequently find in Northern Virginia homes:

- Insufficient cooling or heating performance: e.g., an AC that only cools to 75°F on a hot day suggests it’s low on refrigerant or just too worn out. In a Woodbridge house I inspected, the upper floor was 10 degrees hotter than the main level – a clear sign the 20-year-old AC couldn’t keep up or the ductwork was inadequate. Temperature differentials from room to room can indicate duct leaks or an undersized unit.

- Strange noises or odors: A grinding motor or squealing blower in an older HVAC signals impending failure. A furnace with a faint gas or burning smell might have a cracked heat exchanger or years of dust burning off – both red flags. One buyer in McLean walked away from a home after our HVAC inspection revealed a strong odor of fuel oil from an ancient boiler – they didn’t want the cost and hassle of converting that system.

- Deferred maintenance: We often see very dirty filters, clogged coils, or rusted furnace burners in older homes. This tells a buyer that the system may not have been cared for, accelerating its demise. An inspector from Burgess Inspections notes that it’s “not uncommon for us to find hidden issues in a home’s HVAC system… identifying inefficiencies or deferred repairs”. Such findings will be included in the report and serve as negotiating points.

- Safety issues: The biggest concern with an old furnace is a cracked heat exchanger, which can leak carbon monoxide. While home inspectors do a basic check (like checking for flame disturbance when the blower comes on or testing CO levels), they often recommend having a licensed HVAC pro examine it if the furnace is beyond a certain age. In Virginia, I’ve seen some contracts where if the heat exchanger is found cracked, the buyer can demand a new furnace or cancel, since it’s a serious hazard. Similarly, an old furnace without modern safety controls (no cutoff switches, old mercury thermostat, etc.) might alarm buyers. Virginia law doesn’t mandate sellers to upgrade these if they work, but again, it can become a bargaining chip or cause buyer discomfort.

Northern Virginia Context: Our area has a variety of heating/cooling setups – from heat pumps to gas furnaces with AC, to even oil furnaces in some older Fairfax and Loudoun rural homes. Each has its telltale age issues. Heat pumps, common in places like Fairfax Station and Manassas, often struggle as they age, especially in very cold weather. A buyer from out of state, unfamiliar with heat pumps, might insist on an HVAC specialist’s review to ensure the auxiliary heat is working. In Arlington’s high-rise condos, aging HVAC systems often mean old fan-coil units or heat pump systems in each unit; condo buyers often ask for service records or an HVAC inspection because replacement in a condo can be tricky and costly. Meanwhile, Loudoun County has many larger homes (5000+ sq ft) built ~15 years ago in Brambleton or Leesburg that have multiple HVAC zones. If those original systems are still there, a buyer might face replacing two or three systems in short order – a potential $20k expense – so you bet they will negotiate aggressively after inspection.

Outcomes in Sales: If an HVAC system is found to be at end-of-life but still limping along, what happens? As mentioned, Virginia’s standard contingency doesn’t force a seller to replace a working unit just because it’s old. However, the buyer can use the “unsatisfactory inspection” clause to walk away if they’re not comfortable. Often, though, buyer and seller reach a compromise:

- The seller might agree to service the unit (clean it, tune it, and change the filters) prior to closing to demonstrate goodwill.

- The seller might pay for a one-year home warranty (~$500-600) that covers HVAC breakdowns, giving the buyer peace of mind for the first year.

- A seller might offer a credit (say $3,000) toward replacement, especially if multiple offers aren’t on the table. In slower markets, buyers have more power to demand this.

- In some cases, I’ve seen sellers preemptively replace an old system before listing to avoid any issues – touting “New HVAC” as a selling point. This happened in a Vienna house I consulted on; the owner installed a new heat pump because every nearby sale had buyers asking for it.

From the buyer’s perspective, having a trusted HVAC technician inspect the system during the contingency period is key. They can estimate remaining life and likely repair costs. As one blog for homebuyers noted, “a quick home inspection can determine if the HVAC system is at the end of its life… Catching these issues early may be useful when negotiating price”. I’ve done inspections where, after hearing my report, the buyer successfully negotiated the price down to account for an imminent $8,000 HVAC replacement. If the seller wouldn’t budge, the buyer had to decide if they still wanted the home or to walk away and find something with newer systems.

Conclusion of this Chapter: An aging HVAC system is one of the most common items to spark further inspection and negotiation in a Northern Virginia home sale. It might not kill a deal on its own if both parties are reasonable, but it certainly can complicate it. Everyone recognizes that heating and cooling are big-ticket items. As a seller, it pays to service your units and be upfront if they’re old (maybe price the home accordingly). As a buyer, do your due diligence: ask for maintenance records, look at the unit’s age, listen for odd sounds during the showing, and use that home inspection contingency to get the full story. Knowing the HVAC’s condition can save you from either expensive surprises or help you negotiate a better deal on the home.

Chapter 4: HVAC Functional Problems and Safety Concerns

Why It’s a Problem: Beyond age, an HVAC system may have operational issues or safety hazards that are uncovered during the home sale process. These issues – even in a relatively newer system – can trigger a contingency because they require repair or create uncertainty for the buyer. In Northern Virginia, common HVAC issues include uneven cooling, insufficient airflow, strange noises, evidence of past refrigerant leaks, or furnace safety issues. If a general home inspector notes “HVAC system not performing to standard” or a potential hazard, the buyer will often exercise their right to a specialized HVAC inspection (as allowed in the inspection contingency). I’ve been that specialist on many occasions, coming in after a home inspector flagged something. In one memorable case in Alexandria, the home inspector measured only a 8°F drop across the AC (where 15-20°F is normal). That indicated poor cooling, so the buyer’s contingency allowed an HVAC contractor (me) to conduct a further inspection. We found the system low on refrigerant due to a coil leak. The buyer then had grounds to request a fix or credit, as this was a deficiency affecting the home’s livability.

Specific HVAC Issues Often Found:

- Inadequate Cooling or Heating: Northern Virginia summers can be brutal (95°F+ and high humidity are not rare in July/August), so air conditioning is non-negotiable for buyers. If, during showings or inspections, the AC can’t keep the house cool, it raises alarms. For example, a home in Manassas I inspected had an upstairs that wouldn’t go below 80°F. The culprit was an undersized HVAC system for the addition that was built onto the house. The buyers wrote a contingency that the HVAC must be evaluated and any deficiencies remedied. Indeed, significant temperature differences between rooms or floors can indicate problems with the ductwork or capacity. Similarly, in wintertime transactions, if a heat pump struggles to maintain heat on a cold day (common in older heat pumps around here), buyers get concerned about efficiency or whether a backup heat source is working. These performance issues are “functionally deficient” aspects of HVAC that a reasonable buyer would want fixed before proceeding.

- Unusual Noises or Vibration: A rattling condenser outside a Fairfax home or a screeching blower motor in a Dale City townhouse might seem minor, but they often portend failing components. Inspectors typically will note loud or odd noises. I was once called to a Falls Church house because the inspector heard a loud buzz from the AC compressor – I found that the compressor was grounding out internally (a major failure in waiting). The buyer used this information to insist on a new outdoor unit as a condition to close. Odd sounds can definitely spook buyers; nobody wants to move in and have the HVAC die immediately. So these noises often lead to a repair contingency or a credit negotiation.

- Airflow and Duct Issues: Another common functional problem is weak airflow from vents. This could be due to dirty filters, but in some cases, it’s undersized ductwork or a failing blower. In the context of a sale, if certain rooms (often in older Cape Cod style homes in Arlington or the extended ramblers in Bethesda – just outside VA) don’t get enough airflow, a buyer might worry the HVAC design is flawed. While a home inspector might not catch subtle airflow issues, any obvious ones (like one bedroom has no air coming out at all) will be noted. Buyers might then negotiate for duct cleaning, adding returns, or other improvements. It’s worth noting that sometimes HVAC issues intertwine with other systems – for example, poor airflow might be related to clogged filters or even electrical issues with the blower motor capacitor. So a thorough inspection looks at the system holistically.

- Thermostat and Control Problems: A minor but notable point – if a thermostat is malfunctioning or very old (mercury dial type) and placed poorly, it can cause comfort issues. I’ve seen contracts in which the buyer requests the installation of a modern programmable thermostat before closing. These requests come up especially if the home is higher-end or “smart home” features are expected. In Northern Virginia, tech-savvy buyers in places like Tysons or Reston might see an old thermostat as a red flag that the HVAC hasn’t been updated.

- Furnace and Carbon Monoxide Safety: This is a big one. Every fall and winter, we discover furnace issues during home sales. The most serious is a cracked heat exchanger, which can leak carbon monoxide – an invisible, odorless gas that can be deadly. Home inspectors usually test ambient CO levels and may notice warning signs such as flame distortion. If they suspect a crack, they will recommend a specialist inspection. In Virginia, if a furnace is found to have a cracked heat exchanger, it’s typically considered a material defect (safety hazard) that must be addressed. I’ve been involved in cases in Oakton and Arlington where the buyer’s home inspector’s CO detector went off near the furnace – leading us to find a crack. In each case, the seller had to replace the furnace entirely as part of the deal. No buyer (nor their lender) will proceed with a known carbon monoxide risk. Also, related to this, Virginia law requires smoke detectors in homes (and, though it’s more focused on rentals, most buyers expect working smoke and CO alarms). During the walk-through or inspection, if detectors are missing or expired, buyers often request the seller to install new smoke/CO alarms before closing. It’s a small thing, but it shows how safety issues, even minor ones, are taken seriously. Some states mandate it at the point of sale; Virginia’s approach is more about disclosure and buyer request, but, in practice, no seller wants to argue about a $30 detector and risk goodwill.

- Leaks and Moisture: Air conditioners remove humidity, and condensate leaks are common if the drain lines clog. A home inspector might find water in the emergency drip pan in the attic (common in Loudoun colonials with attic furnaces). That indicates a clog or previous overflow. Any active leak can damage ceilings and is a defect that will need fixing. I recall a Chantilly sale where a ceiling stain under the HVAC closet gave the inspector a tip-off. Turned out the condensate pump had failed, and water overflowed. The buyer’s contingency then required the HVAC be repaired and the ceiling fixed, or no deal.

Negotiating Repairs vs. Credits: When these functional HVAC issues come up, how they’re handled can vary. If it’s a clear repair (like a leaking coil or bad motor), often the buyer will request the seller to remedy the defect by a licensed HVAC contractor prior to closing. Alternatively, the parties may agree on a credit and let the buyer handle it after closing (some buyers prefer this to ensure they get the repair done to their satisfaction). For instance, the leaking coil case in Alexandria I mentioned: the seller gave a $1,500 credit for a new evaporator coil installation, rather than doing it themselves, because the buyer wanted their own HVAC company to do it right after closing.

From the seller’s perspective, some try to preempt issues by servicing the HVAC before listing. Providing a recent service report (“System tuned up and checked OK in May 2025”) can reassure buyers. However, a service is not as in-depth as an inspection – it might not catch a slow freon leak or a partially cracked heat exchanger. So buyers still often insist on their own check if something seems off. Sellers in Virginia are generally not obligated to proactively fix anything that isn’t broken, but they must allow reasonable inspections as per contract. Good listing agents advise their clients: if you know of an HVAC quirk (e.g., “the second floor gets warm; we use fans”), disclose it or address it, because it likely will come up anyway and could sour the buyer if it’s a surprise.

The Cost of Ignoring HVAC Problems: What if a seller refuses to deal with an HVAC issue? Suppose an inspection finds the AC not cooling well and the buyer asks for a fix, but the seller says “No, it works well enough.” The buyer then has a choice per the home inspection contingency: accept it, negotiate further, or terminate the contract. In this competitive market, some buyers might be willing to accept more risk, but many won’t. They might walk and find another house (especially if inventory isn’t too tight). That leaves the seller back on the market, now legally obligated to disclose the known issue to future buyers. This is why I encourage resolution. As a master technician, I often provide written documentation of the problem, which the buyer’s agent can show the seller – basically saying “this is a bona fide issue, not buyer’s remorse.” In Northern Virginia recently, about 15% of pending sales have been falling through (a bit higher than the historical norm), largely due to inspection issues. HVAC problems are part of the overall inspection findings. Sellers have to weigh: is it worth losing a deal over an AC repair? Usually not.

Local Insight: In Arlington County, older homes often had no central air originally and rely on retrofitted systems – which can be funky. For example, I inspected a 1930s bungalow in Clarendon that had a high-velocity AC system installed in the 90s. It wasn’t cooling well, and parts were obsolete. The buyer was coming from out-of-state and really wanted central air. They wrote that the contract would proceed only if the system could be made to cool to at least 72°F upstairs. The seller had to invest in updating the system’s blower and duct insulation to achieve that. In Fairfax’s newer developments, like Fair Lakes or Kingstowne, HVAC setups are more standard but can still have issues like any system. In Prince William’s Gainesville and Bristow areas, two zones are often present; it’s not uncommon for one to be weaker. If one HVAC unit is problematic, it effectively halved the home’s comfort, so buyers treat it seriously. Loudoun’s larger homes also may have extensive HVAC (even geothermal in some high-end ones near Middleburg). A geothermal system not working properly would absolutely require a specialized inspection. The key is: whatever the heating/cooling system type, if it’s not working right or poses a hazard, it becomes a focal point in negotiations.

Safety Note: I’d be remiss not to mention carbon monoxide and ventilation. Northern Virginia building code now requires carbon monoxide detectors in new construction with fuel-burning appliances, and while older homes aren’t forced to retrofit by law, many home inspectors recommend them. I frequently see this as an item in a home inspection report: “Recommend installing CO detectors on each level.” Savvy buyers will then ask the seller to do it. It’s a small but important safety fix – I’ve done it myself for clients during that negotiation phase. Similarly, things like gas furnaces need proper flue venting; if an inspector sees rust or back-drafting around a flue, that’s a safety defect needing repair (maybe the flue is undersized or partially blocked). All these “little” HVAC-related safety issues add up in the contingency conversations.

In sum, functional and safety issues with HVAC systems are a common reason for additional inspections and contract conditions. A home might pass the eye test during a quick showing, but only through inspection does the buyer learn, say, the AC isn’t cooling or the furnace has high CO readings. At that point, it’s critical to address these problems, or the sale could be in jeopardy. Both parties have an interest in resolving HVAC defects: the buyer wants a safe, comfortable home and the seller wants the deal to close. As the technician often in the middle, I strive to provide objective evidence of the problem and sometimes even propose the solution that goes into the contract addendum (e.g., “licensed HVAC contractor to replace evaporator coil prior to closing”). With cooperation, most of these issues can be fixed, allowing the sale to proceed smoothly.

Chapter 5: Code Compliance and Safety Upgrades

Why It’s a Problem: Not every home sale contingency stems from glaring defects; sometimes it’s about bringing a house up to modern code and safety standards. Virginia, like all states, has building codes that evolve over time. A house built in 1985 in Fairfax or Vienna was compliant then, but by today’s codes, it might lack certain safety features (like Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters in bathrooms, or Arc Fault breakers in bedrooms). When selling an older home, these code discrepancies aren’t required to be updated by law if they were legal at the time (they’re usually “grandfathered”). However, they often become negotiation points or buyer concerns once revealed in an inspection. Buyers – especially first-timers or those with young kids – can get nervous about things that aren’t “to code,” even if technically they’ve been functioning for decades. As a master electrician, I frequently get asked by buyers in Northern Virginia to inspect and quote upgrades like adding GFCI outlets, updating electrical panels to current code, or installing smoke detectors in all the right places. While a seller might push back (“It’s worked fine for 40 years!”), Ultimately, if a safety issue is highlighted, addressing it can be key to keeping the buyer on board. In some cases, lenders or insurance companies may also insist on certain upgrades (for instance, some insurance will not issue a policy unless the home has smoke detectors and no known electrical code violations). Thus, code-compliance issues often serve as a soft contingency: the buyer requests them, and the deal might falter if they aren’t met.

[Image of GFCI outlet diagram]

Common Code/Upgrade Issues in VA Home Sales:

- GFCI (Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter) Outlets: These are the outlets with test/reset buttons, required in kitchens, bathrooms, garages, exterior, and other wet areas in modern code. Houses built before the 1970s originally had none; even homes built into the 1980s might not have them everywhere (the requirements expanded over time). Home inspectors in Northern Virginia always check for GFCIs in the proper locations. If they find standard outlets by the kitchen sink or in the bathroom, they’ll note it as a recommended safety upgrade. For example, in an older Arlington Cape Cod I sold, none of the bathroom outlets were GFCI-protected. The buyer didn’t treat it as a deal breaker, but they did request in the Home Inspection Repair Addendum that GFCI outlets be installed in all bathrooms and the kitchen. The seller agreed, since it was a relatively minor cost (a few hundred dollars) and it would be hard to refuse given it’s current safety code. This kind of request is extremely common. Technically, per the Virginia REALTOR® contract language, something like “outlets not GFCI” might be considered a deficiency if it “could affect a reasonable person’s decision to purchase” (some argue it is, some argue it isn’t, since it’s grandfathered). To avoid arguing semantics, most sellers just resolve it. As an electrician, I often get a call during contingencies: “Can you quickly install 6 GFCIs so we can satisfy the buyer?”

- AFCI (Arc Fault Circuit Interrupter) Protection: Newer codes (late 2000s onward) require AFCI breakers (or outlets) on many circuits (bedrooms, living areas, etc.) to prevent fire from arcing faults. Fairfax County, for example, now requires AFCI protection on 15- and 20-amp circuits in most areas of a dwelling. If you’re selling a 1990s house in Chantilly or a 1970s townhouse in Reston, it’s unlikely the panel has AFCIs. Home inspectors don’t always list missing AFCIs as a “deficiency” (since they were code-compliant when built), but some will educate the buyer about them. I’ve seen buyers then ask for an electrical contractor to retrofit AFCI breakers in the panel as a condition. It’s not a cheap upgrade (breakers are ~$50 each, times many circuits, plus labor), so sellers often negotiate around it – maybe agreeing to do a few or offering a credit. One particular sale in Potomac Falls (Sterling) comes to mind where the buyer was an electrician himself; he insisted the seller swap in AFCI breakers for the bedroom circuits or he’d walk, citing fire safety. The seller conceded to a few of them. Even if not mandated, AFCIs are increasingly expected by safety-conscious buyers.

- Smoke and Carbon Monoxide Detectors: Virginia law requires that all homes have smoke alarms, and in rental properties, owners must certify they are present and working. For owner-occupied sales, the law is less direct but building codes require smoke detectors in certain locations in any remodeling. In practice, most Realtors will ensure that, by closing, there are working smoke detectors on each level and in the outside bedrooms. Many Northern Virginia jurisdictions (and certainly home inspectors) also recommend CO detectors if there are any gas appliances or an attached garage. I’ve rarely seen a buyer not ask for missing smoke detectors to be installed – it’s usually handled outside of formal contingencies, more of a “to-do before closing.” But it’s worth noting: if a house lacks proper detectors, an appraiser or FHA/VA loan inspector can flag it too. So it’s in everyone’s interest to have them. As a safety upgrade, it’s a low-hanging fruit that can otherwise delay things (some settlements have been held up until a smoke detector was installed and verified, believe it or not).

- Electrical Service and Panel Upgrades to Code: In Chapter 1, we talked about old 60-amp service panels. Here, I’ll note that local code requirements may apply if an electrical permit is pulled. Fairfax and other local counties require a minimum 100-amp service for any new or renovated home. So if during a contingency the seller agrees to upgrade an old panel (maybe because the buyer’s lender insists), they can’t just put in a 60-amp breaker box again (obviously) – it must be 100 or greater. Often, the recommendation is to go to 200-amp to “future-proof”. I had a case in Herndon where the home still had 60-amp service, and the buyer’s home insurance said they wouldn’t cover it. The contract was amended to require the seller to have a new 200-amp service installed before closing (I did the work). This was essentially a code compliance upgrade triggered by the transaction. Similarly, if a home’s electrical panel is found to be extremely overcrowded or unsafe, sometimes the resolution is “install new panel with sufficient circuits.” While not explicitly required by law until you do it, it becomes a de facto requirement to keep the buyer.

- Ungrounded Three-Prong Outlets: A lot of older homes (50s/60s construction in places like Annandale or Arlington) have two-prong outlets or they were converted to three-prong without actually adding a ground. Home inspectors always test random outlets. If they find ungrounded outlets, it’s flagged as a defect (“open ground”). While this was legal back in the day, today it’s considered a safety issue (no surge protection, risk of shock). Buyers will often request that all three-prong outlets be properly grounded or replaced with GFCI-protected ones where grounding isn’t feasible. I’ve had to go in and rewire a dozen outlets in an Alexandria house to satisfy such a request. It can be a bit involved (sometimes new ground wires need running), but again it’s about safety. Virginia’s stance is that if something is “grandfathered” and functioning, it’s not automatically a deficiency. Yet, an open ground likely would “affect a reasonable person’s decision” if they plan to plug in expensive electronics or just want their kids safe, so buyers treat it as important.

- Staircase and Attic Ventilation Codes (less common): Occasionally, non-electrical/HVAC code issues arise, such as missing handrails or insufficient attic insulation, but those are beyond our scope. However, if an HVAC ties into code – e.g., an old oil furnace with an improper flue or an AC compressor too close to the electric meter (violating clearance) – these could be noted and require correction.

Permit and Inspection Process: An important aspect to remember: if as part of the contingency resolution, significant electrical work is done (panel change, rewire, etc.), it must be done under permit. A buyer will want proof (final inspection sticker or report) that the work was inspected by county authorities. In Northern Virginia, the permitting process can vary slightly by county, but the general rule is any substantial electrical addition/alteration needs a permit and official inspection. I sometimes have to educate sellers on this. They’ll say “Can’t you just swap the panel without a permit? We’re in a rush.” I respond that doing so could jeopardize the sale if the buyer finds out (and ethically, I won’t break the law). Plus, getting the proper sign-offs documents the improvements, which can be a selling point later. It assures the buyer that everything was done correctly. I even call it “cheap insurance” – permits ensure things are up to code and keep your home legal and safe. Most buyers in our area are savvy enough to ask, “Was a permit pulled for that new work?” So compliance is key.

Grandfathering vs. Modern Expectations: Virginia’s disclosure forms require the seller to state that the property is being sold “as-is,” except as otherwise agreed, and that the buyer is responsible for determining whether the property meets building codes (Virginia is somewhat caveat emptor). However, buyers can still request upgrades. There’s a subtle dance: a seller might say no to some upgrade requests by citing grandfathering. For instance, a seller in Franconia might refuse to install AFCIs, arguing it’s not a defect. The buyer then has to decide if it’s worth walking away over that. In a strong seller’s market, buyers might accept more. But in a balanced or buyer’s market, sellers tend to be more accommodating.

Many Realtors will advise their buyers to focus on true defects and hazards in their repair requests, not every little code difference. Thus, the most common safety upgrades that do get agreed on are GFCIs, smoke/CO alarms, grounding issues, and any glaring electrical hazards like exposed wiring or over-fusing. Less common code requirements (like AFCIs, tamper-resistant outlets, or specific NEC updates) might not be pursued unless the buyer is particularly concerned or the house has many issues.

Speaking of tamper-resistant outlets: current code requires new outlet installations be tamper-resistant (to protect kids). If an electrician replaces an outlet today in Fairfax, it must be tamper-resistant by code. Buyers with small children might notice or ask about this, but practically, I haven’t seen a deal hinge on swapping to TR outlets. It’s more of a nice bonus if done during other electrical work.

Why It Matters to Deals: Ultimately, these code and safety updates matter because they affect the perception of the home’s safety and quality. A home that appears up to date with safety features gives buyers confidence. One that looks like a time capsule of bygone building standards might make them hesitate or hold back on spending. I’ve heard of cases where an appraiser for a VA loan required GFCIs to be installed as a condition of the loan funding – effectively forcing the issue regardless of the sales contract terms. If a buyer’s insurance finds out the home has, say, an outdated electrical setup that’s against modern codes (like the earlier example of <100A service or a subpanel wired unsafely), they might issue a binding condition that it be remedied. Those become last-minute contingencies to satisfy.

To avoid last-minute scrambles, many sellers in Northern Virginia now do pre-listing inspections and address these common safety items ahead of time. The National Association of Realtors encourages this: fixing issues like an outdated electrical panel or other safety concerns before listing can help keep deals from unraveling. It’s sound advice I echo to clients.

Conclusion: Code compliance and safety upgrades fall into a gray area in real estate contingencies. They’re not always legally mandated to sell the home, but practically they often must be dealt with to satisfy buyers and their inspectors. As a licensed contractor, I see my role as helping bridge that gap: identifying affordable ways to upgrade safety (like adding GFCIs, bonding gas lines, etc.) so that the buyer feels the home is safe without the seller feeling they’re doing a complete renovation for free. It’s all about risk mitigation – for the buyer, mitigating the future risk of shock, fire, or injury; for the seller, mitigating the risk of losing the sale. When both sides understand that, coming to an agreement on these improvements is usually achievable, and everyone sleeps better at night (literally, knowing the smoke alarms are on and the wiring is done right).

Chapter 6: Home Inspection Contingencies and Deal Breakers

Why It’s a Problem: The home inspection contingency is perhaps the most critical clause in Virginia real estate contracts when it comes to electrical and HVAC issues. It essentially gives the buyer a protected period to investigate the property and either negotiate repairs or back out if unsatisfied. As we’ve explored in previous chapters, a lot can be uncovered in that period – from dangerous wiring to failing HVAC – and these discoveries are in fact the #1 reason deals fall through in today’s market. As a Master Electrician involved in many transactions, I’ve seen how a single inspection finding can flip the script on a sale. A house that went under contract with excited buyers can end up back on the market a week later because the inspection contingency wasn’t resolved. In June 2025, 15% of pending home sales fell through, up from a historical 12% norm, with home inspections the top culprit. This chapter will discuss how the inspection contingency works in Northern Virginia and highlight real cases of electrical/HVAC issues that have caused contract failures or required creative solutions to keep the deal together.

How the Contingency Works (Briefly): In Northern Virginia, we typically use the Virginia REALTORS® standard Home Inspection Contingency Addendum. It gives the buyer a certain number of days (often 7-10 days after ratification) to conduct any inspections they want – general, specific, etc.. The buyer can then do one of three things by the deadline: (1) request repairs or credits for specific deficiencies by submitting a Removal Addendum with the list of issues; (2) declare the contract void (walk away) with a copy of the inspection report; or (3) do nothing and let the contingency expire (which means they accept the house as-is). If they request repairs, there’s a Negotiation Period (usually 3-5 days) for the buyer and seller to agree. If they cannot agree on all items, the buyer often has the right to void the contract after the negotiation period. Importantly, the contract defines “deficiencies” as items that could affect a reasonable person’s decision to purchase, not cosmetic or merely code-update issues. So we’re talking about true problems: safety, function, damage, etc. Everything we’ve covered – from electrical hazards to HVAC malfunctions – easily falls under “deficiency” because they affect habitability and safety.

Now, in practice, what happens when such deficiencies are found?

Scenario 1: The Seller Fixes the Issues (Deal Proceeds): This is the ideal resolution. Say an inspection in Fairfax finds an outdated electrical panel and a leaking AC coil. The buyers submit an addendum requesting “Replace Federal Pacific electrical panel with a new panel by licensed electrician” and “Repair HVAC refrigerant leak and recharge.” The seller, not wanting to lose the sale, agrees. They hire professionals (maybe me for the panel, an HVAC company for the coil) and get it done before closing. Both parties sign off the repairs are done, and the contingency is removed. The sale closes smoothly. This happens a lot, especially when the issues are clear and the market isn’t ultra hot. Sellers know that if this buyer found these issues, the next buyer likely will too, so it’s better to address them now. In fact, the National Association of Realtors says pre-listing inspections are wise because they “allow a seller the opportunity to address any repairs before the For Sale sign even goes up… avoiding surprises like a costly…outdated electrical panel that could cause buyers to bolt”. Proactive sellers in places like Oakton or Leesburg sometimes do these repairs up front for that reason.

Scenario 2: The Seller Credits the Buyer (Deal Proceeds): Sometimes the seller might not want to actually do the work (maybe they’re out of state or don’t have time), or the buyer might prefer to handle it to their own satisfaction. In that case, they negotiate a price reduction or closing cost credit equal to the estimated cost of repairs. For example, in a Herndon deal, the home needed about $4,000 of electrical upgrades (new panel, GFCIs, some wiring fixes). Instead of the seller coordinating electricians, they simply agreed to credit the buyer $4,000 at closing. The buyer was happy because they could then hire whomever they wanted post-closing, and the seller essentially paid for it via a slightly lower net. This approach only works if the lender allows the credit (larger credits can be an issue with loan underwriting limits), but usually a few thousand is fine. It’s a common compromise: the buyer gets money to fix it, and the seller doesn’t have to manage the repair. Realtors often favor this for complex issues so that liability for the repair’s quality transfers to the buyer after closing.

Scenario 3: No Agreement – Deal Falls Through: Unfortunately, there are cases where the parties just can’t see eye to eye. Perhaps the seller thinks the buyer is asking for too much of an “upgrade” rather than a repair, or the buyer is spooked by the extent of the issues. For instance, I consulted on a Springfield home where the inspection revealed aluminum wiring throughout the house and an ancient furnace with a cracked heat exchanger. The buyer got cold feet – they estimated $20k of work needed and the seller only offered $5k credit. Neither would budge, and the buyer terminated the contract within the contingency window (getting their earnest money back). The house went back on the market, now with those defects disclosed to future buyers. That seller eventually sold to an investor at a lower price who was willing to take on the repairs. This shows that when major defects surface, if the seller won’t adequately compensate or remediate, buyers do walk. And thanks to the contingency, they can do so without penalty as long as they follow the proper notice procedure.

Another real example: an older home in Arlington had significant knob-and-tube wiring still active. The buyer wanted it all replaced. The sellers felt it was excessive to rewire the whole house for them (cost ~$15k). They only wanted to install GFCI protection on those circuits as a half-measure. The buyer decided to walk, because they were uncomfortable living with any knob-and-tube (not to mention their insurance quoted a high premium). So that was a deal breaker rooted in an electrical issue.

Emotional and Financial Stakes: When these negotiations happen, it’s not just dollars and cents – there’s emotion. Buyers often feel worried (“Is this house a money pit? Were the sellers hiding something?”) and sellers can feel defensive or drained (“I already came down on price, now they want more?”). Good agents manage expectations: most homes will have some issues, and negotiation is normal. But certain issues have an outsized impact. Anything involving fire or shock risk (electrical) or big-ticket replacement (HVAC or roof) tends to trigger strong reactions. Sellers should know that a buyer’s request for safety fixes isn’t the buyer nitpicking – it’s usually their genuine concern or their lender’s/insurer’s requirement. Conversely, buyers should understand older homes won’t meet new codes in every way and they can’t expect a 1950s house in Falls Church to be made 2020s perfect. The standard is “working and safe.”

The Virginia REALTORS® Legal Hotline has addressed scenarios illustrating these principles. In one case, a buyer tried to terminate because the seller wouldn’t do a cosmetic item (paint the basement) even though the seller agreed to a roof repair. The hotline attorney noted the buyer couldn’t walk just over cosmetic stuff – only true deficiencies justify termination. In our context, electrical/HVAC issues are clearly deficiencies, not cosmetic. If not resolved, termination is justified. Another Legal Hotline Q&A asked if a buyer could back out because an outlet might be faulty (but they had no proof it was actually malfunctioning) – the answer was generally no, without evidence of a material issue, you can’t claim a contingency issue. That underscores the need for buyers to document the issues (inspection reports, photos).

Deal Breaker Examples (Lawsuits and Failures): When things slip through the cracks, it can lead to post-closing conflict. Virginia is somewhat a “buyer beware” state, but there are still legal avenues if a seller willfully hid a material defect. For instance, if a seller knew the electrical panel was overheating and failed to disclose it, a buyer could later sue for fraud. Virginia requires sellers to disclose known material adverse facts about the property’s physical condition. It doesn’t mandate seller-proactive inspections, but if asked or if an issue is known, they can’t lie. I remember a case (reported in a law blog) where buyers sued sellers over undisclosed aluminum wiring that caused a small fire after closing – the crux was whether the sellers knew it was a hazard. It’s hard for buyers to win those, which is why most just ensure to find issues before closing, but it happens. More commonly, if a home inspector truly misses an obvious, critical issue (say, they didn’t notice the furnace was completely nonfunctional and it died immediately after closing), the buyer might claim negligence. Inspectors in Virginia have limits of liability (often the fee), so lawsuits are rare. But just the threat shows how high-stakes these things feel to buyers.

Keeping Deals Together: From my perspective, communication and reasonable compromise solve most problems. I’ve been part of many “deal-saving” moments, like being on the phone with a listing agent explaining that yes, the panel is a fire hazard and really should be replaced, at which point the seller, who was skeptical, agrees once they hear it from an expert. Or telling a buyer that a certain issue looks scarier than it is (maybe some scorch marks in a wire were from an old fixed issue), calming them so they don’t walk. Agents often lean on us contractors for second opinions – a way to mediate between buyer’s inspector and seller’s denial. For example, a seller might say, “That home inspector doesn’t know what they’re talking about – the AC is fine.” So the buyer hires an HVAC pro (from our team) who confirms the problem with data. Then the seller relents because an expert verified it. In one Vienna transaction, our report about a failing heat exchanger convinced the seller to replace the furnace, whereas before he thought the buyer was just being difficult.

Backup Contracts and Market Dynamics: In Northern Virginia’s competitive market, some buyers in recent years waived inspections to win bidding wars (especially in 2021-2022). But many got burned with costly repairs later. Now, as things normalize, inspection contingencies are back and for good reason – they protect buyers. Sellers know if one buyer walks, another may not be as forgiving. So deal failures can lead to stigma: a house that comes back to market after a fall-through often faces skepticism (“what’s wrong with it?”). Sometimes the listing agent will proactively say “previous contract fell out due to buyer financing, not house issues” to combat that. If it was due to inspection, they’ll say “yes the house needs X and seller will do Y” to reassure new buyers.

The bottom line for this chapter: Electrical and HVAC problems are heavy hitters in home inspections. They frequently dictate whether a contract sticks or twists. A pre-listing inspection (and the seller’s subsequent repair of major items) can preempt many surprises. For buyers, having that contingency and using it wisely is their safety valve – it’s better to lose a week of time and the cost of an inspection than to buy a house with a $50,000 unknown defect. As one real estate team put it, “An inspection could reveal serious flaws… If major defects were discovered, it could be a major deal-breaker for the buyer”. Negotiation is the art of turning those deal-breakers into just bumps in the road. Most deals can be saved if both sides approach the issues in good faith, armed with facts and fair solutions. And if not, the contingency provides a no-fault exit, which, though disappointing, is far better than litigation or unsafe living conditions.

Chapter 7: Local County Perspectives: Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, Arlington

Why Local Context Matters: Northern Virginia isn’t a monolith – each county (and independent cities within them) has a unique housing stock, regulations, and common issues. While the broad reasons for electrical/HVAC inspections apply everywhere, mentioning specific towns and areas highlights nuances that might trigger an extra inspection contingency. As someone who has worked across Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, and Arlington, I’ve noticed patterns. This chapter provides a county-by-county glance at common situations where homeowners need these inspections, along with examples from various communities – from the dense urban neighborhoods of Arlington to the rural stretches of Loudoun.

Fairfax County

Profile: Fairfax is Virginia’s most populous county, encompassing a diverse range from urban Tysons Corner high-rises to suburban Reston and Springfield subdivisions, to older areas like Annandale and McLean with mid-century homes. It also includes independent cities like Fairfax City and Falls Church (which have their own governance but share many code practices). Fairfax County is known for well-funded code enforcement and a strict permitting process. They have detailed requirements – e.g., any addition or significant alteration must be permitted, and they emphasize modern safety codes like AFCIs and tamper-resistant outlets in renovations.

Common Inspection Triggers: In Fairfax, many homes were built in the 1960s-1990s due to the population boom. So you’ll see a lot of electrical panel upgrades needed – for instance, houses in Kings Park (Springfield) or Annandale might still have their original 100-amp panels that are now undersized or even the dreaded FPE panels if built in the 70s. It’s routine for home inspectors here to suggest an electrical evaluation on older homes. Fairfax County explicitly notes that any new circuits or panel changes require a permit and inspection, so buyers and sellers are aware that if something is discovered unpermitted, it will have to be fixed properly (or removed). I’ve had several jobs in Fairfax where, during a sale, unpermitted basement wiring had to be brought up to code – one notable one in Burke where the seller finished a basement without permits, and to close the sale we had to open walls and install proper junction boxes as the county inspector required. It delayed closing by two weeks, but got done.

Areas and Examples:

- Older Neighborhoods: Annandale, Falls Church (areas of Fairfax County), Mantua, Lake Barcroft – homes from the 1950s-60s often still have two-prong outlets, possibly some cloth wiring, fuse panels, or early breaker panels. An inspection for a sale in these neighborhoods nearly always raises questions about electrical upgrades. For example, a friend sold a 1955 rambler in Annandale and the buyer’s inspector flagged the ungrounded outlets and absence of GFCIs. We had to retrofit the grounds to the kitchen and install GFCIs – the buyer insisted, and it was reasonable. Also, many of these homes have had additions (Sunroom, second floor, etc.) over the years – verifying that those were permitted, and the wiring is safe, is a big part of due diligence.

- Newer Suburbs: Fairfax Station, Chantilly, Centreville, Reston – lots of 1980s-2000s houses. These typically have modern wiring (grounded, circuit breakers), but now as they age, issues like worn-out HVAC units or occasional aluminum branch wiring (some early 70s parts of Reston) come up. In Reston, many contemporary-style houses built in the 70s originally had electric baseboard heat, and some owners later added HVAC. I’ve seen some creative DIY in that regard, which buyers then ask to have inspected or corrected.

- High-End Areas: Great Falls, McLean, Oakton – large homes, many with extensive electrical systems (home theaters, pools, etc.) and multiple HVAC zones. Buyers here, often paying $1M+, will bring in specialized inspectors (pool inspector, generator inspector, etc.). I was once brought to a Great Falls estate under contract because it had a whole-house generator and complex HVAC, and the buyer wanted an expert check beyond the general inspection. We found the generator transfer switch was improperly installed (unpermitted work) – a potentially big issue if not fixed, so it became a condition that the seller have it corrected (costly, but the deal size was large enough).

- Fairfax City (independent city within Fairfax County’s orbit): Fairfax City homes follow similar codes. One twist: some older sections of Fairfax City have homes from the 1940s where knob-and-tube might hide. A home I worked on near Fairfax High School had half the circuits updated and half still old – that sale got complicated until the seller agreed to rewire the remaining knob-and-tube.

In Fairfax, building authorities like to see things done right. A permit closed in Fairfax is like a stamp of legitimacy. Thus, buyers often explicitly ask: “Were permits obtained for that finished basement or that new HVAC?” If not, they might ask the seller to get a post-facto permit inspection or at least provide a letter from a licensed contractor that it’s safe. I’ve provided such letters after thoroughly inspecting a system, essentially saying “I certify the electrical work in XYZ area is safe and meets code as far as visible” to calm a buyer’s fears when no permit record existed.

Loudoun County

Profile: Loudoun was once very rural but has seen explosive growth since the 1990s, especially in Ashburn, Sterling, Leesburg, South Riding, Brambleton, etc. Eastern Loudoun is now suburban and tech-centric (data centers and all). Western Loudoun remains rural with historic towns (Middleburg, Purcellville) and farms. The housing stock is thus a mix of brand-new developments and very old homes (Civil War-era houses in some villages). This dual nature means inspection issues can vary widely.

Common Inspection Triggers:

- In the eastern suburbs (Ashburn/Sterling area), most homes are 10-30 years old. They generally have good electrical systems (copper wiring, 200A panels) from the start. But now, in 2026, a house built in 1996 has a 30-year-old furnace/AC and perhaps builder-grade electrical parts reaching end of life. I see HVAC contingencies frequently in Loudoun – e.g., an Ashburn Farm colonial with original HVAC will prompt a buyer to inspect it and possibly request a new system or credit, because summers in Loudoun get hot and no one wants an AC failure out there where humidity is high.

- Another thing: Loudoun had a lot of polybutylene plumbing in 90s homes (outside our scope, but it’s analogous to aluminum wiring but for plumbing – deals have contingencies around that too). The reason I mention is if a house has one material issue like that, buyers often scrutinize the electrical too (“what else is lurking?”).

- In historic Western Loudoun (think Waterford, Hillsboro, older Leesburg), houses from the 1800s or early 1900s often have been updated over time, but it’s not uncommon to find a mix of wiring methods. I inspected a 1890s farmhouse near Lovettsville; it had a modern 200A service but still had some knob-and-tube feeding attic lights and an old well pump. The buyer’s offer became contingent on a full electrical re-inspection and upgrade by a licensed electrician (me). That was a significant negotiation because the seller was an estate that didn’t want to pay; ultimately they split the cost. Out in these areas, well and septic systems also come into play (with separate inspection contingencies), but electrically one unique thing can be the well pump circuit or septic pump – if those aren’t up to code or functioning, it’s both a health and electrical concern.

- Loudoun County building services also require permits, but enforcement might have historically been a bit laxer in rural areas. Some remote homes have all sorts of DIY wiring in barns or workshops. I saw a barn in Lincoln, VA that had an extension cord literally running from the main house for power – the buyer obviously balked at that and required a proper sub-panel installation as a condition.

Areas and Examples:

- Ashburn & Sterling: These are dense with late-90s and 2000s homes. Many have dual-zone HVAC (two units). Common scenario: one HVAC was replaced recently, the other is original – so an inspection report says “Unit #2 is 20+ years old, recommend budget for replacement.” Buyers might ask for a credit or a new unit. Also, a lot of townhouses here built quickly in the boom – sometimes we find loose neutral wires or panel issues (not rampant, but I’ve been called for a “panel buzzing” in an Ashburn townhouse during an inspection).

- Leesburg: Leesburg has both an old historic core and large subdivisions from 80s-2000s (like Lansdowne in the 2000s). In older Leesburg houses (like around King Street), knob-and-tube or dated electrical is common. Many are protected historic homes, so renovations had to be careful, but I suspect some had DIY work hidden to avoid approvals. A buyer of a 1930 house in downtown Leesburg I worked with demanded an electrical inspection; we found a mix of modern Romex and old cloth wiring still active. It became a contingency that the seller contribute to rewiring. In the newer parts, the focus is more on whether systems have been maintained; e.g., “Has the HVAC been serviced annually? Show records.” They might not bring a specialist if everything appears in order, but if the home inspector sees anything off (rusty furnace, open junction boxes), they will recommend further evaluation.

- South Riding & Brambleton: Very new communities (2010s and up). Typically fewer issues due to age. However, interestingly, newer homes sometimes have more technology integrated – smart thermostats, solar panels, EV chargers – which can be additional inspection items. For example, if a house has a Tesla charger in the garage, a buyer might ask, “Is this properly installed with permit?” as part of their contingency. I inspected a home in Brambleton where the previous owner had installed a massive home theater system with a dedicated subpanel – no permit. The buyer was an audiophile and insisted on a thorough check of that setup. It turned out fine, but it shows the breadth of what can come up.

- Middleburg/Purcellville (Rural Loudoun): As touched on, older wiring and also often generator systems (power outages are more common out there, so many homes have standby generators or at least transfer switches for portable ones). These need to be inspected too. I recall a Purcellville buyer concerned about an outbuilding’s wiring – we found it was powered via an undersized underground feed that was not in conduit. That was a code violation; the buyer required it be properly rewired or they’d walk. The seller in that case opted to just disconnect power to the outbuilding and reduce the price slightly, rather than trench a new line. The buyer accepted because their main concern was safety.

Loudoun’s permit process is robust now, but some older homes slipped through cracks. Buyers know this, so they dig hard during contingencies. Also, Loudoun’s environment (some areas have no natural gas, so heat is electric or propane) can be a factor. Electric heat can be expensive and if a house only has baseboards, buyers might negotiate to have at least a heat pump installed. That’s not exactly code-required, but a sale in Lovettsville fell through, I heard of because the buyers didn’t realize the beautiful farmhouse had no central HVAC at all – once they did, they wanted the price dropped by $30k to install one; the seller refused, thinking someone else would be fine with it. It eventually sold to cash buyers who were fine (maybe they liked wood stoves).

Prince William County

Profile: Prince William, including cities of Manassas and Manassas Park, has a mix of older development near DC (like Woodbridge, Dale City – lots of 1960s-70s starter homes) and newer communities further out (Gainesville, Bristow – houses from 2000s in the expansion era). It also has some rural pockets and historic areas (e.g., around Manassas Battlefield or Occoquan). The county is a bit more moderate in housing cost, so many first-time buyers land here, which means they may rely on FHA/VA loans that have stricter property condition requirements.

Common Inspection Triggers:

- In the older areas (Woodbridge/Dumfries): Many houses might have had additions, enclosed carports, etc. done over time. I’ve seen plenty of subpar DIY in these. For example, a carport converted to a family room in Dale City but the wiring was still running off an exterior circuit – definitely flagged in inspection. These areas also still have some homes with fuse panels or early breaker panels. Replacement of Federal Pacific panels is a big issue here; I get calls all the time for “I’m selling my Woodbridge house and the inspector says I have to change my FPE panel.” Indeed, a Prince William County electrician or home inspector will rarely let an FPE or Zinsco slide – they know the risks (house fires have happened in the area due to them). Federal Pacific panels have caused fires and should be replaced as soon as possible if found, and buyers usually insist on it.

- Prince William also has many townhouses (especially in areas like Lake Ridge, Montclair). Townhouses built in the 70s often had aluminum wiring and 100A service. I was involved in a Lake Ridge townhouse sale where the buyer’s inspector found aluminum branch wiring – the buyer’s insurance wouldn’t cover it unless remediated (pigtailed or replaced). The contingency became that the seller pay for an electrician (me) to do COPALUM crimps on all outlets (a recommended fix for aluminum wiring). That cost around $2,000 and delayed closing a bit while we waited for materials, but it saved the deal. In townhouse/condo settings, if one unit has a fire risk, it can affect neighbors, so buyers are quite cautious.